ManikarnikaGhat from the Ganges. The terraced buildings to the left and center are pilgrim sheds. The domed temple to the right, now abandoned, was built in the 18th century by Queen Ahalya Bai Holkar of Indore

It’s always six o’clock at Manikarnika. Squinting through the thick smoke of incinerating bodies, one can see the clock atop the decrepit Birla pilgrim shed which hasn’t moved in living memory. Shrouded in perpetual twilight, legend states here, at this most holy of Hindu sites on the banks of the Ganges, time never runs down but instead stands still. And so it does. Precariously rooted in the ashes of thousands of bodies burned over thousands of years, the site is reverently known as the “cradle of Vishnu.” Its origins, rumored to extend back to the beginning of creation, serve as a gruesome yet persistent reminder of life’s trembling fragility and temporary essence. Here within the ancient sacred city of Varanasi, multitudes of the Hindu pious have for millennium brought their dead to this auspicious place for cremation and ultimately their final journey from this world. Their presence and force is palpably felt within the all enveloping spectral haze. It is a place of great severity and immense profundity.

Manikarnika is one of 84 ghat, (Sanskrit for “step”), areas perched on the northern side of the Ganges River as it forms a crescent shape through the north-central Indian city of Varanasi. Built of large stone blocks, these magnificent tiers run continuously for a distance of four miles. Beginning at the historic confluence of the Asi and Ganges rivers in the south they boldly stretch to the meeting of the Ganges and Varana rivers to the north. Considered sacred by the Hindus, each section atop the ghats possesses its own name, history, mythology and religious activities. Most ghats have their own shrines or temples which for legendary and supernatural reasons are considered to be divine tirthas. A tirtha is a mystical “touch point” where the fabric of physical reality reputedly intersects with other metaphysical and spiritual dimensions.

Looking west from Manikarnika at Dashashmaveda Ghat. The orange structure in the center is the long abandoned Prayaga temple

From deep within the river the ghats rise. Like ancient, hardened roots linking the city to its soul they hold and invigorate the faith and devotion of millions. Curving to the horizon they seem timeless, transcendental, infinite. Countless generations have experienced both the initiation of life and the arrival of death in their shifting saffron shadows. Where the mortal and immortal meet, they are the grand stage of the spirit from which the narration of life is spun. Within Varanasi, the sacred city of Shiva, all the ghats are considered holy. However, Manikarnika is regarded as the holiest of all.

The legend of Manikarnika is as seductive as its reality extreme. As told in the grandiloquent tones of the sacred Kashi Kandra; there was once a time when nothing existed. Darkness was everywhere. There was no time, sound, sensation or direction. There was only “Pure Reality” in the form of Brahmin, the Hindu God of creation. Once Brahmin decided to create “another”, and this other took the form of Shiva, known from then on as the “Formless One”. Shiva lived in the forest of bliss and one day decided it would be nice to create another being who would form the world, bear its burdens and protect it. He thus made Vishnu and endowed him with the epitome of all good qualities. Shiva instructed Vishnu to create everything on earth in accordance with the sacred Vedas. In compliance Vishnu immediately began a series of “severe austerities”. Using his discus he scooped out a beautiful lotus pond and filled it with the water from his own sweat. Motionless, Vishnu sat on the edge of this pond for 500,000 years performing his austerities.

Looking east from Manikarnika from the steps of Bhonsala Ghat. In the upper right hand side is the Mosque of Aurangzeb, the last Mughol ruler of Varanasi

Eventually Shiva looked in on Vishnu and was impressed with the degree of his devotion. As a reward Shiva told Vishnu he would grant him any wish he might have. Vishnu humbly requested he only be allowed to live in the divine presence of Shiva forever. Shiva trembled with delight over the great devotion showed by Vishnu and his jeweled earring, “manikarnika”, fell from his ear into the pond. Hence forward this pond would be called Manikarnika. So pleased with Vishnu was Shiva he decided to grant him another wish. Vishnu decided because the earring of Shiva had been “let go” and fell here, his second wish was that all creatures should also be “let go” or liberated at this place. Vishnu also requested that all kinds of worship, charity and sacrifice yield “moksha” or liberation here in what would be known as Manikarnika. Shiva happily agreed and the site became endowed with all the characteristics that are claimed to exist to this day.

Moksha is liberation, or specifically freedom from the cycle of reincarnation. When moksha is achieved an individual upon death will no longer be returned to suffer the pains and uncertainties of human existence. With moksha the “soul” or human essence is thought to transpose to eternal residence in a great idyllic realm. Though Hinduism has many, often conflicting, sacred texts, all agree on the fundamental premise that to die in Varanasi is an automatic qualification for moksha. The Puranas, with typical Vedic hyperbole, advise pilgrims visiting Varanasi to “smash their feet with a stone on arrival lest they be tempted to leave.” It’s further maintained only in Varanasi will Shiva whisper the taraka mantra, (the prayer of the crossing,) in the ear of the deceased at the moment of death. This prayer supposedly destroys the consequences of past actions resulting in immediate liberation. Though there are many other ways by which one may secure the promise of liberation, dying in Varanasi is considered a certainty. However, should one not die in Varanasi but elsewhere, being cremated at Manikarnika also guarantees hearing the taraka mantra and being liberated from future lives. As such, families from all over India make the journey to Manikarnika to insure ultimate peace is bestowed upon their loved ones after death.

Visiting Manikarnika requires one to first travel through the dark, labyrinthine lanes of the old section of Varanasi known as the pucca mahal. Narrow and paved with uneven rocks drenched in raw sewage, they wind between ancient, crumbling buildings of brick and mud that have changed little in the last 1,500 years. Here reality seems tinged with a darkened surreal and unworldly quality. Overloaded, rickety wooden carts drawn by exhausted and emaciated pack animals vie for space with the multitudes of impoverished residents who tenuously exist in this pre medieval state. Dense, foul smelling air potently stifles all sound and resonance within these shuttered slivers of space. Though devoid of sunlight, the relentless searing heat filters easily, draining the vitality from all who pass through this sultry ether on their way to the ghats. Virtually every wall is pocked with irregular carved niches occupied by tiny shrines or stone representations of some of the 330 million deities who reputedly call this city home. And what representations they are. Crudely malformed with multiple legs, arms, eyes and fangs painted in once vibrant colors, now dimmed by time, they seem to penetrate the darkest realm of the human psyche with their power and presence. Though surrounded by images of the dismal and bizarre one nevertheless senses the palpable presence of the unseen and divine with every labored step.

Nearing Manikarnika one sees many signs of the distinct activities that occur there. The first are the growing number of wooden “stretchers” being manufactured along the way. Approximately five feet in length and consisting of bamboo poles lashed together with twine resembling a crude ladder, the bodies of the dead are tied to these makeshift objects and transported to Manikarnika for burning. Whether the corpse is carried to the top of the ghat by hand, car or rickshaw, the final descent down the steps to the river requires their use. Many barbers loiter about looking for work as the shaving of the head and trimming of the nails is an important part of the cremation ritual.

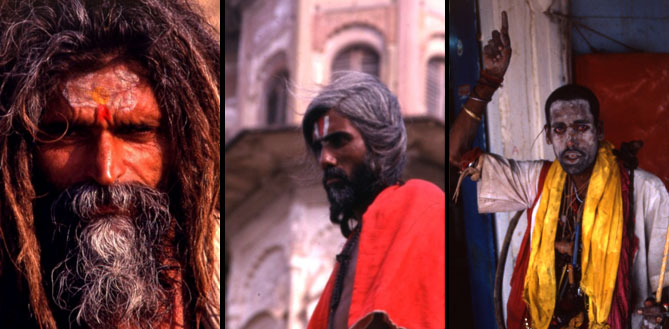

Like ascending from the pit, making the final turn through the city and scaling the last hill into the light at the top of the ghat one of the world’s most dramatic collections of unusual people gradually appears. As Varanasi is considered the holiest city in India it attracts many of the country’s most peculiar and outlandish of sadhus, or holy men. These ascetics represent the extremes of curious and otherworldly appearance and behavior. Drawn to the ghats to be nearer their gods, sadhus, also known as professional mystics, are the living embodiment of many ancient yet diverse religious traditions. Whether quietly offering their prayers to the deities or engaging in extraordinary and bizarre forms of mental and physical austerities, these spiritual seekers vividly demonstrate the wide spectrum of religious expression practiced within the Hindu faith. Some sects demand very little of their sadhu. Those of the Kutichak must only bath twice a day, wear a single vertical forehead mark, shave their hair once a year and survive on food begged from others. Others such as those of the Awadhoota sect wear no clothing, cover their bodies in cremation ash, never cut their hair and may only eat and move like a snake, slithering about on their stomachs without the use of their gradually atrophying arms or legs. Other sects may require members to perform such austerities as standing on one leg with an outstretched arm twenty four hours a day for twelve years or other such tortuous practices. The ghats are filled with thousands of such people. Manikarnika is one of their favorite haunts as the presence of a sadhu is often required to properly perform the cremation ritual and provides them numerous commercial opportunities.

Three sadhus found on Manikarnika. The man on the far left wears a tilak, or forehead decoration suggesting an affiliation with one of the local Vaishnava, (those that worship Vishnu), sects, possibly the Paramhansa. The three vertical stripes on the man in the middle mark him as a member of an unspecified Shaiva group, (those that worship Shiva). The man on the far right has just finished rubbing ashes on his face. He wears a number of talismans around his neck, many of which are inconsistent or contradictory to one another. He wears no tilak so one can assume he is not a member of any particular group but follows his own unique spiritual calling.

Holy cities draw more than just holy people. As giving alms is a standard practice associated with many Hindu rituals those in most dire need of charity also gravitate to Varanasi. The top of the ghats, Manikarnika in particular, are crowded with some of the most pathetic examples of corporeal existence imaginable. Hunger and disease of every variety are gruesomely displayed by the heart rending mobs of beggars whose wretched survival hangs on the generosity of religious pilgrims who come to the ghats. Most simply lie on the squalid street staring upward, too handicapped or infirmed to stand or speak. Dozens of disfigured lepers silently waste along both sides of the path. A greater compendium of misery would be hard to find. It is said those of this pitiable crowd at least have the good luck to die in Varanasi should their quest for assistance fail.

The most visible portent of the imminent appearance of Manikarnika are the numerous bodies, wrapped mummy like, lining the streets awaiting cremation and the heavy, smoke laden air filled with the oddly compelling smell of burning flesh. It is unmistakable and all encompassing. Moving closer, the streets become thicker and thicker with fine ash, padding and muting one’s footsteps as if walking on a soft beach. Considered to be “polluted” ground, the cremation area in most Indian cities is located far from the centers of activity. However, in Varanasi it lies in the middle of town and is considered holy. Here death is seen as the greatest of divine blessings.

Arriving at the top of the ghat and looking towards the river, a ghostly scene unfolds. Framed on three sides by two leaning and dilapidated guest houses, known as pilgrim sheds, their pale yellow paint now encased in oily soot and a long deserted small temple with three fluted domes, Manikarnika seems an amphitheater of death. Unlike the other ghats, here there is no color on any of the forms or surfaces. Amid the perpetual smoke an eerie murkiness and flatness of tone hangs over all- a study in grey and sepia. Bodies wrapped in dull white cloths nestle softly in the heavy ash that covers the stairs or bob aimlessly in the river below. Cows and goats wander unchecked across the steps. The sky is filled with giant crows, the darkened breath of Shiva himself. The sharp rhythmic pounding of heavy hammers on iron wedges can be continuously heard as thin, muscular men split the massive logs that will soon form the pyres. Wood is everywhere. Arranged in unsteady stacks as high as twenty feet, it is piled along every wall and jammed in every conceivable nook. People in white clothing move with silent certainty up and down the stairs, exercising prescribed rituals. All about, oblivious to ceremony or sentiment, perched on their haunches tending the fires like the minions of the dark are the Doms, the “untouchable” keepers of Manikarnika.

Wood is piled for cremations on the center steps of Manikarnika while families and mourners prepare for the rituals

Stepping around the deep legendary pond created by Vishnu’s discus, (now concrete lined,) and moving past a circular marble slab said to contain the footprints of the deity himself, haunted moans emanate from the blackened interior of the pilgrim sheds. The last stop in life, here the sick and aged are brought to die. As death in Varanasi means the immediate attainment of moksha, people from all over travel here when they sense their demise is near. Tilting towards the river, each floor resembles a large open landing area with tattered and filthy rags hung from weathered poles over the openings. Inside the sheds, hiding in shadows from the thin penetrating light, lie the bodies of the dying. In a suffocating haze of heat and insects, mattresses and blankets cover every inch of floor without pattern or order. People rest wherever there is space. The clamor and sounds from the outside streets fails to disturb the stifling silence within. The air is heavy with a sense of anticipation and the smell of mildew and decay. Shrouded women tend to the guests, bringing water, lighting incense and chasing away the impatient rats and stray dogs. In the sheds one never waits long for death. None are merely sick, all are imminently terminal.

Cautiously edging down the steps of Manikarnika, one sees additional sacred representations, all of which still command attention and reverence. Little niches filled with statues of various deities, stone phallus’ of varying sizes called linga, (the most common representation of Shiva,) and miniature shrines holding offerings of garlands and rice are everywhere. Ornately carved suttee stones, their tops gently protruding from under the ash litter the dreary landscape. Suttee is the ritual act of suicide where a widow joins her husband in the flames of his pyre. When committed by an auspicious woman, a decorative marker or stone was frequently placed on the precise spot of the cremation.

In front of Manikarnika the Ganges is filled with both boisterous and mournful activity. The site’s sacred nature entices many to come perform their morning bathing rituals in its shadows. They do so in gleeful abandon with no concern for the somber proceedings behind them. However, on the ghat itself all is desperately quiet. Hindu belief is firm about the tradition of silence afforded the dead. Even the crying of mourners or widows is prohibited and those unable to comply are brusquely removed by the Doms or an officiating sadhu. Swaying loosely in the slow flowing water, clumsy wooden barges from the hinterland crowd the shoreline delivering huge quantities of wood to be later chopped by the Doms into smaller pieces for the pyres. Smaller oared vessels drift from one side of the thickly polluted river to the other, their lone pilots either scattering the ashes of the recently cremated or unceremoniously dumping the bodies of those too poor to afford cremation directly into the holy Ganges. The river itself is commonly filled with bodies in various stages of decay, both human and animal. Unable to bear the cost of a sheet to wrap the corpse or a sadhu to officiate, some families simply place the exposed body directly into the river. Liberation is a much greater gift than any of the material or ceremonial trappings available from life. Often whole families swim across the river from the East, floating a corpse in front of them toward Manikarnika. Hindu tradition is quite explicit that those cremated on the East side of the river across from the ghats are as cursed in the afterlife as those who die in Varanasi are blessed.

A Shaiva shrine on the north end of Manikarnika. On the back wall are carvings of Surya, the Aryan sun god, Shiva and his wife Parvati, Nandi the bull who is the vehicle of Shiva and Ganesh, Shiva’s elephant headed son. With its ornate carving and fluted arches this is one of the more conspicuous shrines found anywhere on the ghats

A large, nameless tirtha containing a number of different linga. A symbol of the energy and power of Shiva, the linga is set in a conical base known as a yoni, a female symbol. The empty niches on the wall once contained icons long since disappeared

For days I watched the procession of the dead at Manikarnika. Daylight or darkness matters not, the fires never die. Despite the myriad of ceremonial differences within the Hindu faith most of the dead on Manikarnika are treated in much the same manner. Initially the wrapped corpse is taken down to the Ganges for one final immersion. Those male mourners present take turns scooping up water from the river in a small vessel and pouring it over the mouth area of the deceased. The body is then removed from the bamboo stretcher, the shroud pulled away and ultimately placed on the pyre. At this time the chief mourner, (always dressed in white,) will bathe in the river and have one of the available barbers shave his face and trim his nails. Once completed the mourner purchases a burning log from the Doms and places it in his right hand. After completing one revolution around the corpse he lights the wood directly under the head. To the accompaniment of the sadhus whispered mantras those assembled begin to sprinkle sandalwood and other fragrant spices over the flames as an offering to Agni, the Vedic deity of fire whose cooperation is said to be “greatly appreciated.”

After about three hours the body is fully consumed with the exception of the skull. The conclusion of the cremation ritual requires the chief mourner to take a bamboo stave and smash the still smoldering skull open. Called kapalakriya, this action is thought to release the soul or preta which is believed to be contained within. Many sects feel the skull breaking is crucial. They believe for ten days after the cremation the preta is still alive and wanders about the vicinity of the chief mourner and his family. A newly released preta is thought to be rather belligerent. If the preta is to finally achieve the status of a revered ancestor, or pitr, small gifts and prayers must be offered to it over the next ten days. If this is not done properly the preta will remain a ghost which can haunt and disrupt the routines and life cycles of its family for eternity. To have a rouge preta hanging around is very dangerous as one never knows when it will inflict death or misfortune upon its relations. However, if the rituals are adequately performed, after ten days the preta transforms into a pitr who will now protect and bestow good fortune upon all concerned.

Once complete, the chief mourner extinguishes the fire with water drawn from the river, pours some over his shoulder with the left hand and leaves the ghat without looking back. Frequently at this stage the barber will hand the chief mourner a large stick or iron rod to use as protection from the preta on the way home as sometimes they have been known to attack. My informants could provide no precise figures as to how often this occurs. After the ceremony is complete, the Doms spring into action one more time. They first collect the remaining ashes for disposal into the Ganges then begin the charming practice of sifting through them in search of anything valuable that may have been left behind or exposed through the process of incineration.

A group of mourners surround a body prior to cremation. In the foreground two Doms sift through the ashes of a previous cremation

As a member of an intensely secular society where the realities of death are routinely cloaked in discreet, sanitary and euphemistic ritual the activities upon Manikarnika seemed most unusual. However, watching the burning pyres heat the remains of the dead, transforming them into the smoke that would ultimately diffuse and assimilate into the atmosphere, I sensed a symmetrical and profound meaning within these events. I must confess to holding pronounced reservations as to the idyllic fate promised to people of virtue upon death by most world religions. However, I found strongly appealing the immediacy and infallibility by which this cremation ritual unifies the dead with the essential elements of existence. The raging fires excited within me a certain relief of spirit as, reminded of a grander universal scheme, my cosmic insignificance transformed from apprehension into comfort. I was reminded ultimately we are all bound by forces greater than society and the rule of human law. Owing to the wide range of interpretation given Manikarnika and Hindu cremation ritual it is difficult to assert specifically how the devout of India relate to this most holy area. Accepting the inconsistency in individual interpretation and meaning it still remains evident this particular locale is very important to the way Hindus conceptualize the relationship between themselves and their gods. On this sacred place is reinforced the notion of a way of life and a method of ordering the cosmos stretching back thousands of years and a powerful reminder of a human commonality transcending geographic and cultural difference.

So beautifully written! I relate profoundly with the article – as I have been trying to write something in my own words since I got back from Varanasi… and this is a very clear description of Manikarnika.

You are definitely right

For days I watched the procession of the dead at Manikarnika…